first posted here

Digital natives with a cause: the future of activism or slacktivism? Maesy Angelina argues that the debate is premature given the obscured understanding on youth digital activism and contends that an effort to understand this from the contextualized perspectives of the digital natives themselves is a crucial first step to make. This is the first out of a series of posts on her journey to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism through a research with Blank Noise under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.

The last decade has witnessed an escalating interest among academics, policy makers, and other practitioners on the intersection between youth, activism, and the new media technologies, which resulted in two narratives: one of doubt and the other of hope. The ‘hope’ narrative hinges on the new plethora of avenues for activism at the young people’s disposal and the bulge of the population, stating that the contemporary forms of youth activism represent new ways of conceiving and doing activism in the present and the future (see, for example, UN DESA, 2005). The ‘doubt’ narrative, on the other hand, questions to what extent the digital activism can contribute to broader social change (Collin, 2008) and some proponents of this view even call it ‘slacktivism’, stating that online activism is only effective if accompanied with real life activism (Morozov, 2009).

Before assessing the potentials of youth’s digital activism to contribute to social change, it is imperative to first gain a comprehensive understanding about this emerging form of activism. A brief review of existing literature on the topic found that most of the analyses are centered on three perspectives, each with its own approach, strengths, and weaknesses: the technology centered, the new social movements centered, and the youth centered perspectives.

The technology centered perspective places a great emphasis on the instrumental role of the internet and new media (see, for instance, Kassimir, 2005; Shirkey, 2007; Brooks and Hodkinson, 2008). It discusses how internet savvy young people are able to exercise their activism differently, because the technology can remove obstacles to organizing, provide a new platform for visibility and make transnational networking easier. In this perspective, the Internet and new media technologies are seen as enabling tool sand the web is viewed as a new space to promote activism. However, this perspective mainly stipulates that there is already a formulaic form of activism that can be transferred from the actual, physical sphere to the virtual arena; it does not consider that the changes caused by the way the youth are using technologies in their daily lives may also create new meanings and forms of activism. This perspective is the most dominant in literature on the topic, being the lens used by the pioneering studies on youth, Internet, and activism.

The new social movements centered perspective goes beyond that and looks at how new meanings and forms of politics and activism are created as the result of the way people are using new media technologies and the Internet. This perspective is leading the recently emerging literature on the topic and emphasizes on the trend of being concerned on issues related to everyday democracy and the favour towards self organized, autonomous, horizontal networks (for examples, see Bennett, 2003; Martin, 2004; Collin, 2008). However, this perspective treats young people merely as ‘vessels’ of the new activism and neglect to examine how their lives have been shaped by the use of new media technologies and the Internet.

The youth centered perspective, represented for example by Juris and Pleyers (2009), acknowledges that ICTs have always been part of young people’s lives and that it intersects with other factors in shaping how they conceive politics and activism. Most of the studies in this perspective were done with youth activists in existing transnational social justice movements, such as the global anti-capitalism or environmental movements. Nevertheless, this perspective mainly views youth activists as ‘becomings’ by defining them as the younger layer of actors in a multi-generational group that will be future leaders of the movement. There are very few researches on autonomous youth movements that are created and consist of young people themselves and look at the youth as political actors in its own right. In addition, the majority of studies also focused on the youth as individuals but not as a collective force.

In addition to the shortcomings of each perspective, there are also common gaps in the current broader body of knowledge on the intersection of youth, new media technologies, and activism.

Firstly, existing researches tend to define activism as concrete actions, such as protests and campaigns, and the values represented by such actions. It neglects other elements that constitute activism together with the actions and values, such as the issue taken up by the action, the ideologies underlying the formulation of action, and the actors behind the activism (Sherrod, 2005; Kassimir, 2005). Divorcing these elements from the analysis gave only a partial view of what youth digital activism is.

Secondly, the majority of studies zoomed into the novelty of new media technologies and how they are being used as a point of departure to investigate the topic. This arguably stems from an adult-centric, pre-digital point of view, which overlooks the fact that internet and new media has always been ‘technology’ for most young people just as how the radio and television have always been ‘technology’ for the previous generation (Shah and Abraham, 2009). This way of thinking divorces the ‘digital’ from the ‘activism’ in digital activism; consequently, it ignores all the other factors that are causing and shaping youth activism and fails to capture how youth actors themselves are viewing or giving meaning to this digital activism.

Finally, researches on the issue skew excessively on developed countries. It must be acknowledged that the ‘digital divide’, or the unequal access to and familiarity with technology based on gender, class, caste, education, economic status or geographical location, in developing countries is deeper and that the digitally active youth are a privileged minority. Yet, a neglect to understand their activism also means a failure to understand why and how the elite who are often perceived to be politically apathetic are engaging with their community to create social change.

The weaknesses identified above demonstrate that our understanding on this particular form of contemporary youth activism is currently obscured. Hence, the two narratives of ‘hope’ and ‘doubt’ lose their relevance given that the subject of assessment, the digital youth activism, is not even clearly understood.

Based on the above overview of the limitations, it is imperative to find a new way to approach to understand the phenomenon of digital youth activism. I will explore the possibilities of such an approach with the following arguments as the starting point.

Firstly, I argue that the key limitation lies on the adult-centric perspective in viewing youth’s engagement with new media technologies, thus what is essential is to go beyond the ‘digital’ and focus on the ‘activism’ part of youth digital activism. Secondly, I argue that exploration of the issue from the standpoint of the youth political actors themselves is crucial to counter the adult-centric perspective dominating the literature on this topic. Thirdly, since so many researches divorce the youth from the context of their activism, it is crucial to focus on a particular case study to a tease out the nuances of youth digital activism.

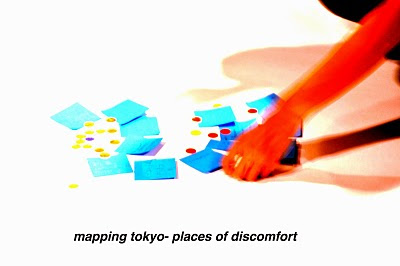

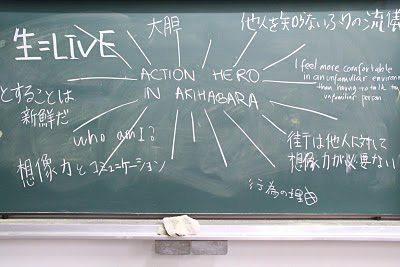

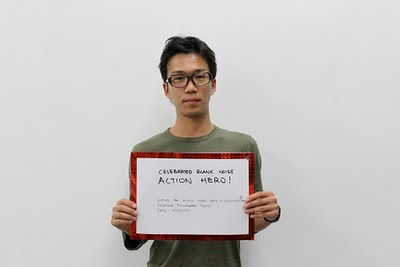

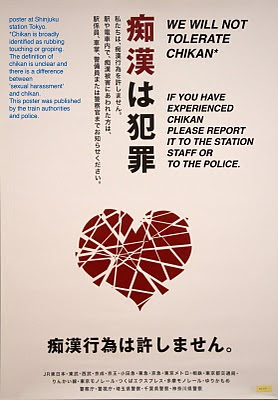

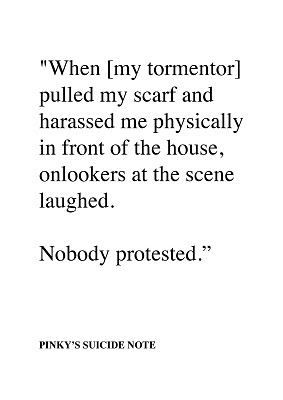

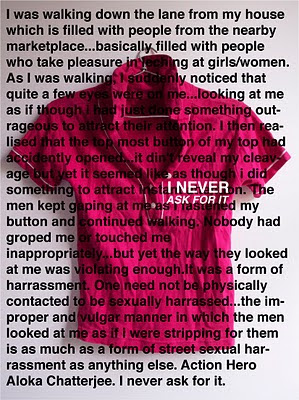

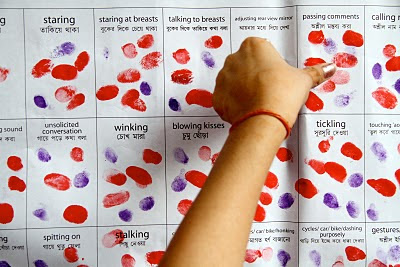

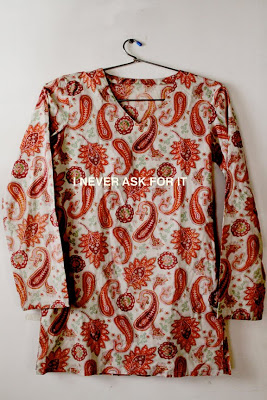

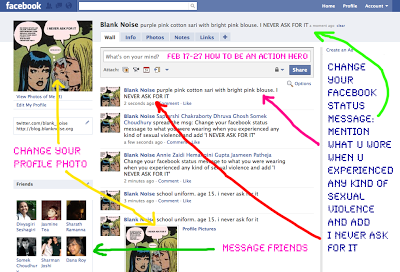

I have the opportunity to explore the approach through a study with Blank Noise, an initiative to address the problem of street sexual harassment in public spaces that originated in 2003 in Bangalore. It has since expanded into nine cities in India with over 2,000 volunteers, all young people between 17-30 years of age. Known for their unique public art street interventions as well as their savvy online presence, Blank Noise was also chosen because its growth and sustainability over the past seven years are a testament to its legitimacy and relevance for youth in India.

The research does not aim to assess the contribution of Blank Noise to social change nor does it claim to represent all forms of youth digital activism in India. Rather, it aims to offer insights on one of the forms of digital natives joining forces for a cause. The research is interested in the following questions: how do young people involved in the Blank Noise articulate their politics? Who are their audience? What are their strategies? What is their conception of the public sphere? How do they organize themselves? How do they represent themselves to others? How do they see and give meaning to their involvement with the Blank Noise? How can we make sense of their initiative? While ‘activism’ is the popular term that is also used in this research, is their initiative a form of activism or is it something else altogether? More importantly, how do these young people define it by themselves? For the next few months, I will share stories, questions, and reflections that emerge along my journey of exploring those questions with Blank Noise on the CIS blog.

This is the first post in the Beyond the Digital series, a research project that aims to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism conducted by Maesy Angelina with Blank Noise under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.