First posted here

By Maesy Angelina in the Digital Natives

After going ‘beyond the digital’ with Blank Noise through the last nine posts, the final post in the series reflects on the understanding gained so far about youth digital activism and questions one needs to carry in moving forward on researching, working with, and understanding digital natives.

Throughout the series, I have argued the following points. Firstly, the 21st century society is changing into a network society and that youth movements are changing accordingly. I have outlined the gaps in the current perspectives used in understanding the current form and proposed to approach the topic by going beyond the digital: from a youth standpoint, exploring all the elements of social movement, and based on a case study in the Global South – the uber cool Blank Noise community who have embraced the research with open arms. The methodology has allowed me to identify the newness in youth’s approach to social change and ways of organizing. Although I do not mean to generalize, there are some points where the case study resonates with the broader youth movement of today. In this concluding post, I will reflect on how the research journey has led me to rethink several points about youth, social change, and activism.

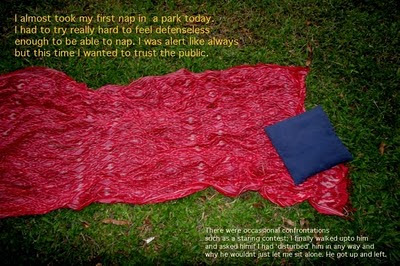

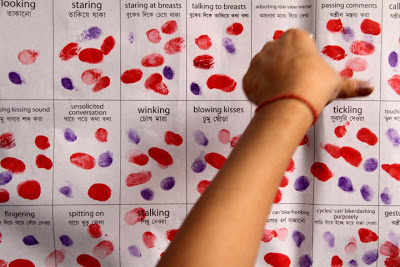

While social movements are commonly imagined to aim for concrete structural change, many youth movements today aim for social and cultural change at the intangible attitudinal level. Consequently, they articulate the issue with an intangible opponent (the mindset) and less-measurable goals. Their objective is to raise public awareness, but their approach to social change is through creating personal change at the individual level through engagement with the movement. Hence, ‘success’ is materialized in having as many people as possible involved in the movement. This is enabled by several factors.

The first is the Internet and new media/social technologies, which is used as a site for community building, support group, campaigns, and a basis to allow people spread all over the globe to remain involved in the collective in the absence of a physical office. However, the cyber is not just a tool; it is also a public space that is equally important with the physical space. Despite acknowledging the diversity of the public engaged in these spaces, youth today do not completely regard them as two separate spheres. Engaging in virtual community has a real impact on everyday lives; the virtual is a part of real life for many youth (Shirky, 2010). However, it is not a smooth ‘space of flows’ (Castells, 2009) either. Youth actors in the Global South do recognize that their ease in navigating both spheres is the ability of the elite in their societies, where the digital divide is paramount. The disconnect stems from their acknowledgementthat social change must be multi-class and an expression of their reflexivity in facing the challenge.

The second enabling factor is its highly individualized approach. The movement enables people to personalize their involvement, both in terms of frequency and ways of engagement as well as in meaning-making. It is an echo of the age of individualism that youth are growing up in, shaped by the liberal economic and political ideologies in the 1990s India and elsewhere (France, 2007). Individualism has become a new social structure, in which personal decisions and meaning-making is deemed as the key to solve structural issues in late modernity (Ibid).

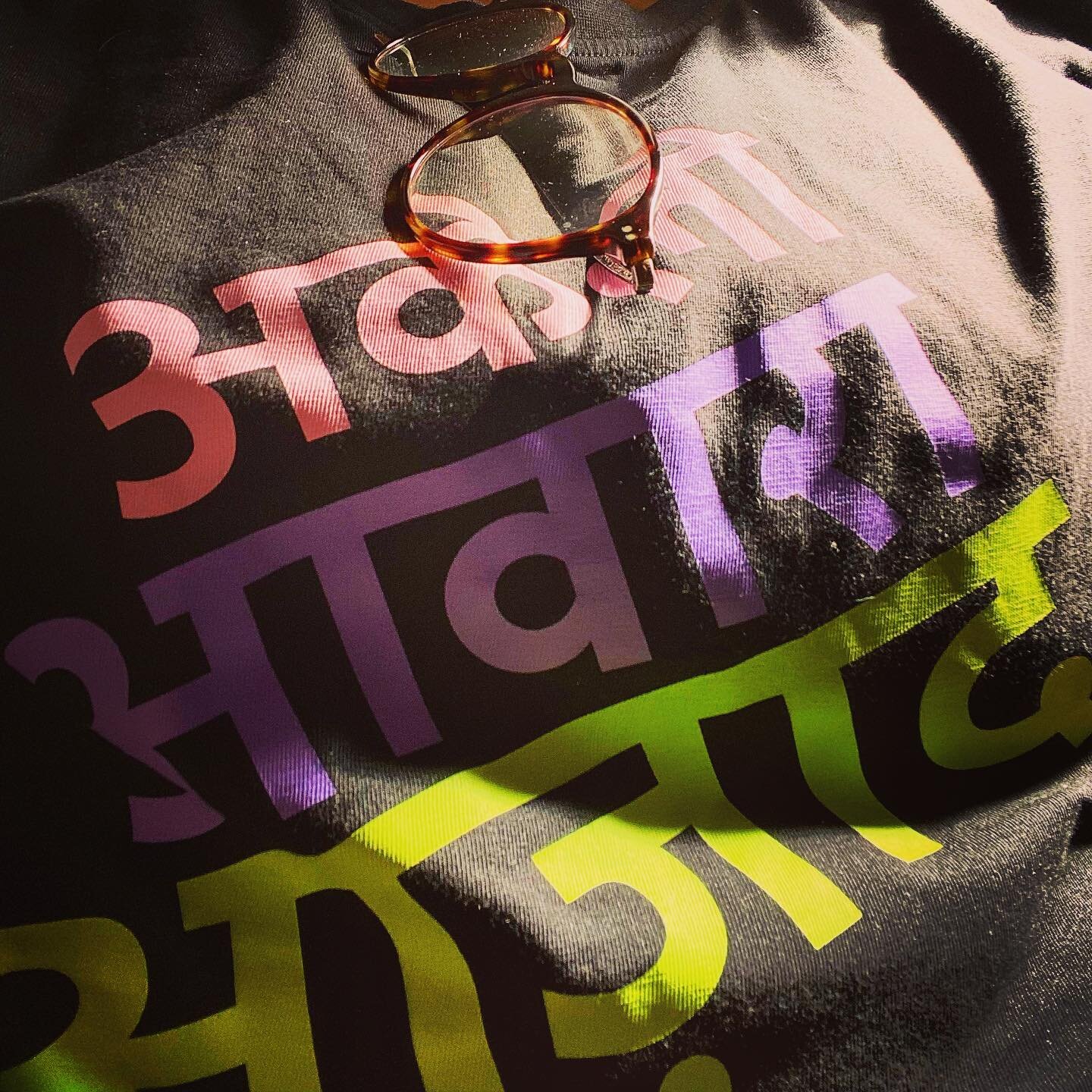

In this era, young people’s lives consist of a combination of a range of activities rather than being focused only in one particular activity (Ibid). This is also the case in their social and political engagement. Very few young people worldwide are full-time activists or completely apathetic, the mainstream are actually involved in ‘everyday activism’ (Bang, 2004; Harris et al, 2010). These are young people who are personalizing politics by adopting causes in their daily behaviour and lifestyle, for instance by purchasing only Fair Trade goods, or being very involved in a short term concrete project but then stopping and moving on to other activities. The emergence of these everyday activists are explained by the dwindling authority of the state in the emergence of major corporations as political powers (Castells, 2009) and youth’s decreased faith in formal political structures which also resulted in decreased interest in collectivist, hierarchical social movements in favour of a more individualized form of activism made easier with Web 2.0 (Harris et al, 2010).

A collective of everyday activists means that there are many forms of participation that one can fluidly navigate in, but it requires a committed leadership core recognized through presence and engagement. As Clay Shirky (2010: 90) said, the main cultural and ethical norm in these groups is to ‘give credit where credit is due’. Since these youth are used to producing and sharing content rather than only consuming, the aforementioned success of the movement lies on the leaders’ ability to facilitate this process. The power to direct the movement is not centralized in the leaders; it is dispersed to members who want to use the opportunity.

This form of movement defies the way social movements have been theorized before, where individuals commit to a tangible goal and the group engagement directed under a defined leadership. The contemporary youth movement could only exist by staying with the intangible articulation and goal to accommodate the variety of personalized meaning-making and allow both personal satisfaction and still create a wider impact; it will be severely challenged by a concrete goal like advocating for a specific regulation. Not all youth there are ‘activist’ in the common full-time sense, for most everyday activists their engagement might not be a form of activism at all but a productive and pleasurable way to use their free time - or, in Clay Shirky’s term, cognitive surplus (2010).

Revisiting my initial intent to put the term activism under scrutiny, I acknowledge this as a call for scholars to re-examine the concepts of activism and social movements through a process of de-framing and re-framing to deal with how youth today are shaping the form of movements. Although the limitations of this paper do not allow me to directly address the challenge, I offer my own learning from this process for the quest of future researchers.

The way young people today are reimagining social change and movements reiterate that political and social engagement should be conceived in the plural. Instead of “Activism” there should be “activisms” in various forms; there is not a new form replacing the older, but all co-existing and having the potential to complement each other. Allowing people to cope with street sexual harassment and create a buzz around the issue should complement, not replace, efforts made by established movements to propose a legislation or service provision from the state. This is also a response I offer to the proponents of the aforementioned “doubt” narrative.

I share the more optimistic viewpoint about how these new forms are presenting more avenues to engage the usually apathetic youth into taking action for a social cause. However, I also acknowledge that the tools that have facilitated the emergence of this new form of movement have existed for less than a decade; thus, we still have to see how it evolves through the years.

Hence, I also find the following questions to be relevant for proponents of the “hope” narrative. Social change needs to cater to the most marginalized in the society, but as elaborated before, the methods of engagement both on the physical and virtual spaces are still contextual to the middle class. Therefore, how can the emerging youth movements evolve to reach other groups in the society? Since most of these movements are divorced from existing movements, how can they synergize with existing movements to propel concrete change? These are open questions that perhaps will be answered with time, but my experience with Blank Noise has shown that these actors have the reflexivity required to start exploring solutions to the challenges.

The research started from a long-term personal interest and curiosity. In this journey, I have found some answers but ended up with more questions that will also stay with me in the long term. As a parting note before, I would like to share a quote that will accompany my ongoing reflection on these questions.

My advice to other young activists of the world: study and respect history... but ultimately break the mould. There have never been social media tools like this before. We are the first generation to test them out: to make the mistakes but also the breakthrough.

(Tammy Tibbetts, 2010)

This is the tenth and final post in the Beyond the Digital series, a research project that aims to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism conducted by Maesy Angelina with Blank Noise under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.